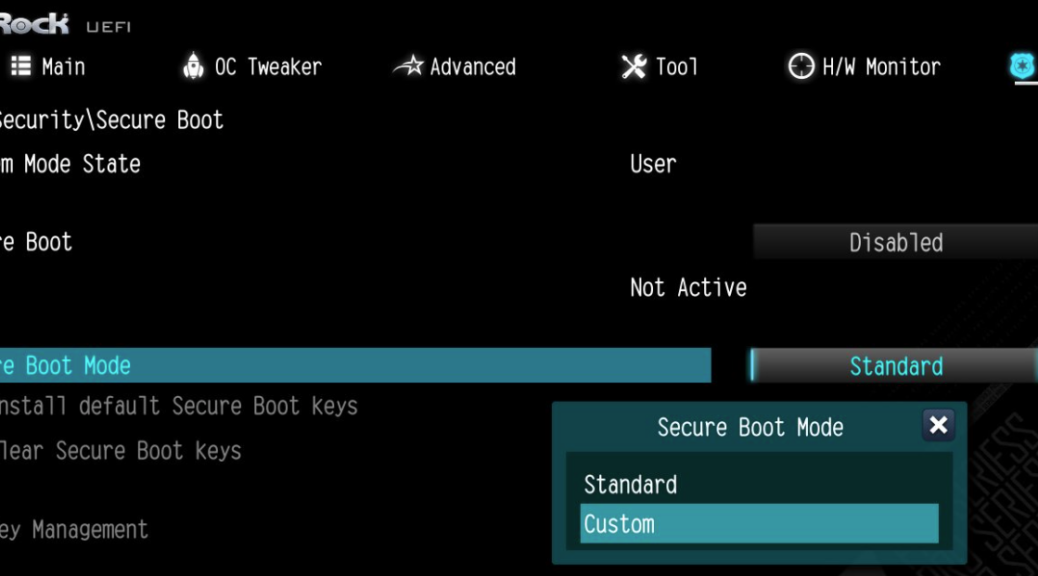

If you look back at my recent bloggage, you’ll see that I spent far too much time recently jumping into and rooting around in UEFI. Specifically, I found myself exposed to the oddities of the Asrock UEFI, which turns out to be finicky in many unexpected ways. Among many other bits of techno-trivia, I learned that my keyboard can’t send function key events to UEFI. I also learned that my logitech mouse sometimes is detected as (!) SATA storage during device enumeration at bootup. So, I’m sprucing up my desktop peripherals to steer clear of those issues. Let me explain…

Why I’m Sprucing Up My Desktop Peripherals

Function keys are helpful and even necessary during inital PC start for access to UEFI. They also drive many functions inside UEFI (e.g. F10 to “save & exit”). When the UEFI can’t read them, it’s anywhere from mildly annoying to maddening. My trusty old MS Comfort Curve 4000 (CC) is what’s known as a “composite USB HID device.” Alas, during POST and UEFI handoff, some PC firmware (including Asrock’s) handles only basic HID devices, not composite ones. To make that stuff work, in other words, I have to use a keyboard different from the CC. Sigh #1.

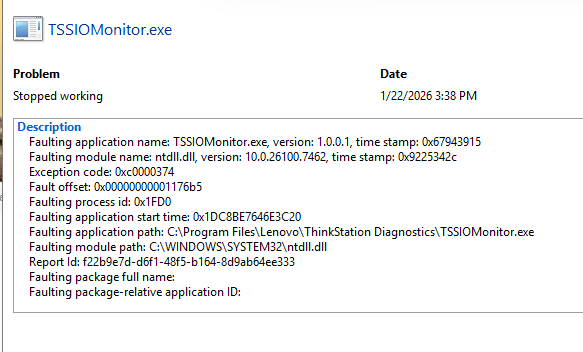

The older Logitech Unifying transceivers that work with mice and keyboards of that era also show another Asrock firmware quirk. They may sometimes (but not always) be recognized as SATA storage devices during first-time device enumeration. This threw me into an endless cycle of A6 POST errors on the B550 when I was trying to get the upstairs machine working last week. Here again, switching to a wired mouse fixed that issue. Sigh #2.

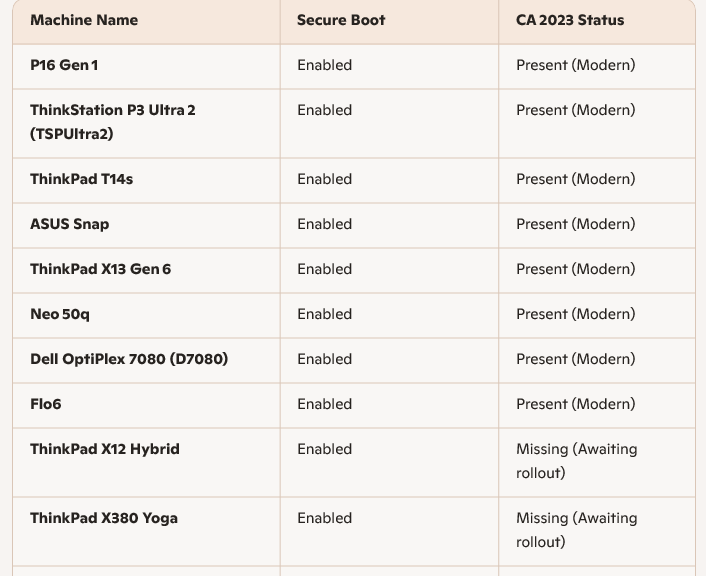

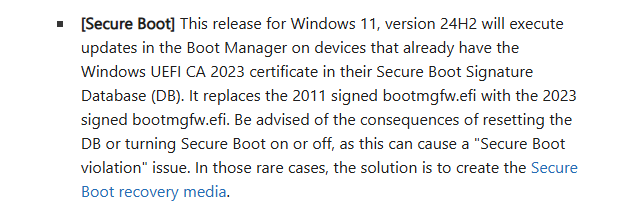

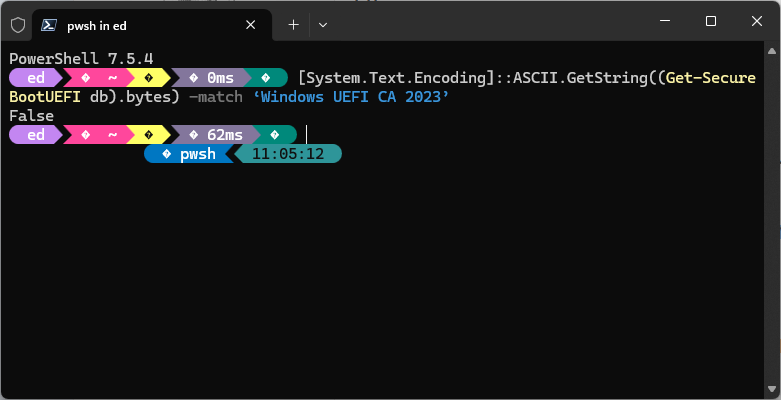

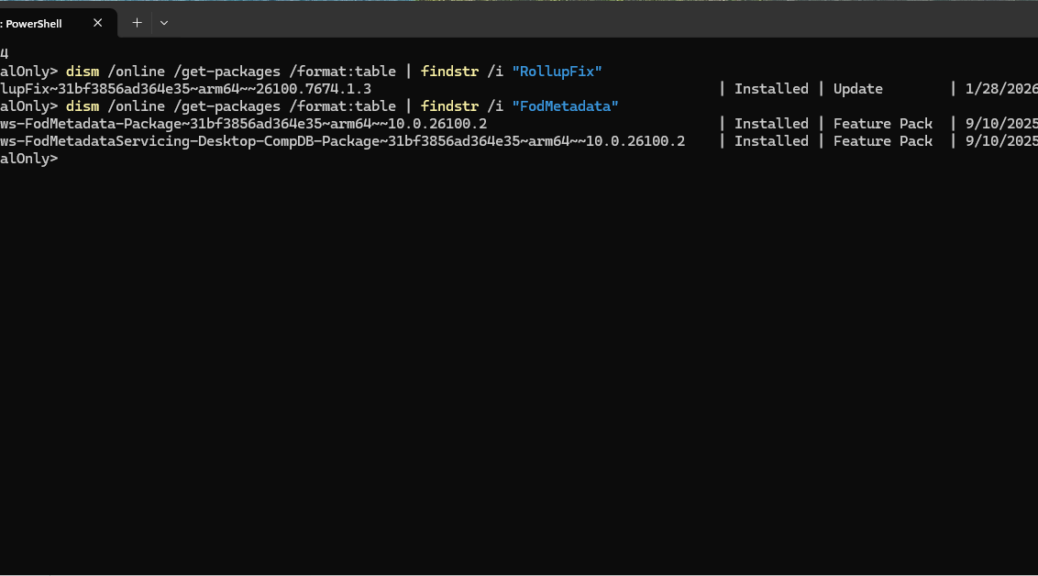

New Secure Boot, New Accoutrement

My fundamental problem is that I’m recycling old gear on a newer system. So it’s time to buy something new to bring it more in synch with the demands of modern UEFI, Secure Boot certificates, TPM 2.0 and suchlike. After walking thru my options with Copilot I’ve chosen a couple of Logitech items (I’m a long-time fan, and reviewed lot of their peripherals in the 2000s for Tom’s Hardware):

- Logitech Wavekeys keyboard (PN: YR0096) mostly matches the CC layout and feel, and is a basic HID device. Thus, its Fn keys should work properly in POST and UEFI.

- In the same box, a Logi Bolt transceiver (xcvr PN: CU0021) which is supposedly superior to the old unifying xcvr, nor subject to mis-detection as a SATA device.

- Logitech Signature M650 mouse (PN: MR0091) mostly matches the MS Mobile Mouse 4000 downstairs and the Logi mouse upstairs. Also works with Logi Bolt xcvr so I need only one transceiver for both devices.

I used the Bolt xcvr from the keyboard, so it came up instantly. I had to download and install the Logi Options+ app to get it to recognize the mouse through that same xcvr (it shipped with one of its own). But that was fast and easy, and the wireless link is quick and accurate. Alas, I got down on wireless keyboards back in the 2000s when I had a bad experience with transmission lag. If you type reasonably quickly (I’m at least 40 wpm or better) that’s not acceptable. So far, so good, with these Logitech devices.

Change is a watchword here in Windows-World. Like it or not (and I’m still figuring that out) my peripherals are changing. So are lots of others things. Adapt and thrive is the plan…