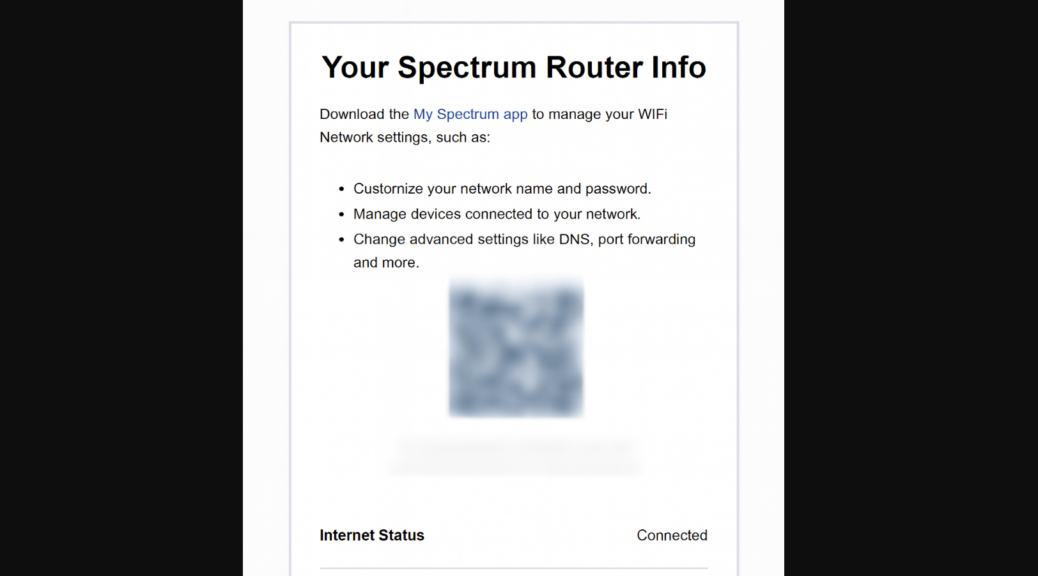

Sometimes, the biggest obstacles in tech aren’t the bugs in your code. Rather, they’re the invisible hands meddling with your network traffic. I recently ran into one such gremlin while trying to install the .NET Core 3.1 Desktop Runtime on a Windows machine. What should have been a simple download turned into a multi-device diagnostic rabbit hole, all thanks to a Spectrum-supplied SAC2V1A router and its overzealous filtering behavior. After I looked intently at its behavior, this spectrum router roadblock diagnosed itself through its (lack of) formatting. It was weird, though…

Once Spotted, This Spectrum Router Roadblock Diagnosed

Things started innocently enough. I needed the .NET Core 3.1 Desktop Runtime for a legacy app. I grabbed the download URL from Microsoft’s official archive and pasted it into Chrome. Instead of a download prompt, I got a blank page with a single, cryptic line of text:

GatewayExceptionResponse

This was odd: it included no HTTP error code, no branding or sourcing, and no explanation. Just that one-liner. I tried again in Edge. Same result. Then I fired up PowerShell and used Invoke-WebRequest. Still the same string. At this point, I suspected something was intercepting the request — but what?

The Plot (or Confusion) Thickens…

I tried the same URL on a second Windows machine. Same result. Then on an iPad. Still blocked. That’s when the lightbulb went off: this wasn’t a device issue. It was a network issue. To test the theory, I pulled out my iPhone, disabled Wi-Fi, and switched to 5G cellular. Then came the real test: typing a 60-character URL — a delightful mix of letters, numbers, and dashes — into Safari by hand. No copy-paste. No QR code. Just raw thumb labor. After a few typos and some muttered curses, I finally got it right. And lo and behold, the file loaded just fine.

Now I knew for sure whence this anomaly issues. The file wasn’t broken or MIA. Microsoft’s Content Delivery Network wasn’t off the air. Clearly, this was a problem coming from the LAN, right at the boundary.

A Ray of Light Shines on the Culprit

With a bit of digging, I discovered the culprit: Spectrum’s Security Shield. This cloud-managed feature is baked into the SAC2V1A router. It’s designed to protect users by blocking malicious or suspicious content. Unfortunately, it seems to think that downloading an out-of-support Microsoft runtime from a legacy CDN is suspicious enough to warrant a silent block.

Let me explain what “silent block” means here. Instead of an HTTP error code or an explanatory “I can’t do that, Dave” message, Security Shield simply emits the string:

GatewayExceptionResponse

No HTML document, no context, no wrapper of any kind. It looks like some kind of escaped error message, in fact. Here’s the real gotcha: one can’t manage this router’s behavior from the web interface anymore. One has to do it through an Android or iPhone mobile app. For the nonce, I’ll forgo that dubious privilege (though I could tackle it on the iPad, where I can at least run an external Bluetooth keyboard). Now that I know what I’m seeing, and why, I can live with this once-in-a-while weirdness.

If This Happens to You…

Should you ever see GatewayExceptionResponse pop up in tiny print at the upper left-hand corner of an otherwise blank browser, you’ll know what it means. The router is gatekeeping what it thinks is a dangerous resource from entering your LAN. I found a different download source (dotnet.microsoft.com) and grabbed what I needed. You should be able to sniff out an alternative if you really need it. If you don’t this could be your clue to leave it alone.

And boy, howdy, is that ever the way things occasionally go in Windows-World. You ask for something, and get a cryptic response in return. Then, you figure out what it means and go forward from there. Case closed!